When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

A VINTAGE PHOTO MEASURING

8 X 10INCHES DEPICTING

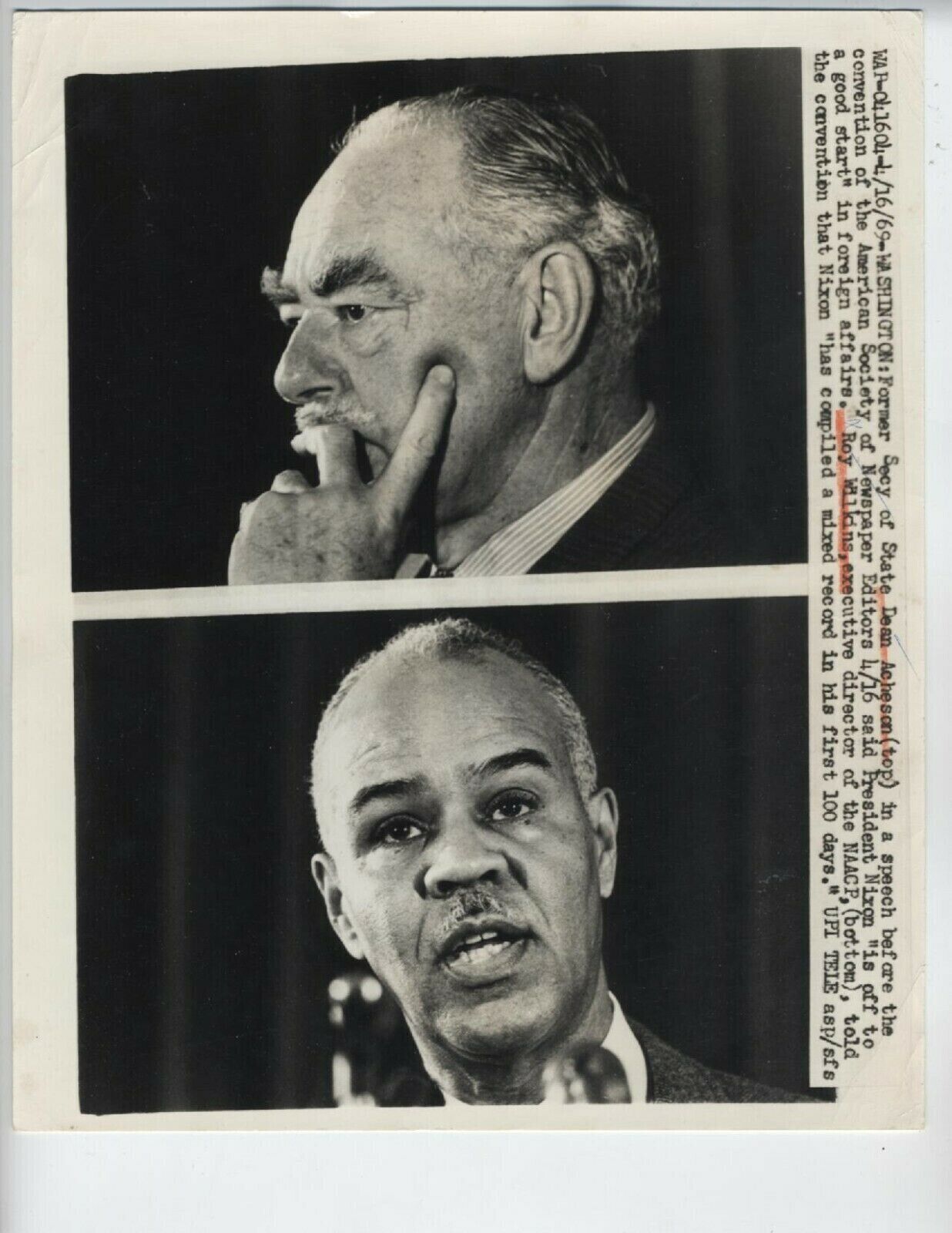

CIVIL RIGHTS 1969 PHOTO DEPICTING FORMER SECTY AND ROY WILKINS EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF THE NAACP

Roy Ottoway Wilkins (August 30, 1901 – September 8, 1981) was a prominent activist in the Civil Rights Movement in the United States from the 1930s to the 1970s.[1][2] Wilkins' most notable role was his leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); in which he held the title of Executive Secretary from 1955 to 1963, and Executive Director from 1964-1977.[2] Wilkins' was a central figure in many notable marches of the civil rights movement. He made valuable contributions in the world of African American literature, and his voice was used to further the efforts in the fight for equality. Wilkins' pursuit of social justice also touched the lives of veterans and active service members, through his awards and recognition of exemplary military personnel.[3]Contents1 Early life2 Early career3 Leading the NAACP4 Views5 Stance on War and Military Involvement6 Legacy7 See also8 References9 Further reading10 External linksEarly lifeWilkins was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on August 30, 1901.[4] His father was not present for his birth, having fled the town in fear of being lynched after he refused demands to step away and yield the sidewalk to a white man.[4] When he was four years old, his mother died from tuberculosis, after which Wilkins and his siblings were raised by an aunt and uncle in the Rondo Neighborhood of St. Paul, Minnesota, where they attended local schools.[5] His nephew was Roger Wilkins. Wilkins graduated from the University of Minnesota with a degree in sociology in 1923.[4]

In 1929, he married social worker Aminda "Minnie" Badeau; the couple had no children of their own, but they raised the two children of Hazel Wilkins-Colton, a writer from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Early careerWhile attending college, Wilkins worked as a journalist at The Minnesota Daily and became editor of The Appeal, an African-American newspaper. After he graduated he became the editor of The Call in 1923.

His confrontation of the Jim Crow Laws led to his activist work, and in 1931 he moved to New York City as assistant NAACP secretary under Walter Francis White. When W. E. B. Du Bois left the organization in 1934, Wilkins replaced him as editor of The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP. From 1949 to 1950, Wilkins chaired the National Emergency Civil Rights Mobilization, which comprised more than 100 local and national groups.

He served as an adviser to the War Department during World War II.

In 1950, Wilkins—along with A. Philip Randolph, founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and Arnold Aronson,[6] a leader of the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council—founded the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights (LCCR). LCCR has become the premier civil rights coalition, and has coordinated the national legislative campaign on behalf of every major civil rights law since 1957.

Leading the NAACP

Roy Wilkins as the Executive Secretary of the NAACP in 1963In 1955, Roy Wilkins was chosen to be the executive secretary of the NAACP, and in 1964 he became its executive director. He had developed an excellent reputation as an articulate spokesperson for the civil rights movement. One of his first actions was to provide support to civil rights activists in Mississippi who were being subjected to a "credit squeeze" by members of the White Citizens Councils.

Wilkins backed a proposal suggested by Dr. T.R.M. Howard of Mound Bayou, Mississippi, who headed the Regional Council of Negro Leadership, a leading civil rights organization in the state. Under the plan, black businesses and voluntary associations shifted their accounts to the black-owned Tri-State Bank of Memphis, Tennessee. By the end of 1955, about $300,000 had been deposited in Tri-State for this purpose. The money enabled Tri-State to extend loans to credit-worthy blacks who were denied loans by white banks.[7] Wilkins participated in the March on Washington (August 1963) which he helped organize.[2] This march was dedicated to the idea of protesting through acts of nonviolence, something that Roy Wilkins was a firm believer in. [8] Wilkins also participated in the Selma to Montgomery marches (1965), and the March Against Fear (1966).

He believed in achieving reform by legislative means, testified before many Congressional hearings and conferred with Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter. These achievements gained Wilkins attention from government officials and other established politicians, earning him respect as well as the nickname, "Mr. Civil Rights". [9] Wilkins strongly opposed militancy in the movement for civil rights as represented by the "black power" movement due to his non-violence principles. He was a strong critic of racism in any form regardless of its creed, color, or political motivation, and he also declared that violence and racial separation of blacks and whites were not the answer.[2] As late as 1962, Wilkins criticized the direct action methods of the Freedom Riders, but changed his stance after the Birmingham campaign, and was arrested for leading a picketing protest in 1963.[10]

On issues of segregation, as well, he was a proponent of systematic integration instead of radical desegregation. In a 1964 interview with Robert Penn Warren for the book Who Speaks for the Negro?, he declared,

We Negroes want the improvements in the public school system – and among them, of course, the elimination of segregation, based upon race – the institution of the same quality education in the schools attended by our children as those attended by other children, and we want Negro teachers and we want Negro supervisors, and we want all the opportunity, but the only way our form of government and our structure of society can survive is by some common indoctrination of our citizenry, and we have found this in the public school system. And, for any reformer, black or white, zealot or not, to come along and say, "I'll destroy it, if it doesn't do like I want it to do," is very dangerous business, as far as I'm concerned.[11]

However, these moderate views increasingly brought him into conflict with younger, more militant black activists who saw him as an "Uncle Tom".

Wilkins was also a member of Omega Psi Phi, a fraternity with a civil rights focus, and one of the intercollegiate Greek-letter fraternities established for African Americans.Wilkins (right) with Sammy Davis, Jr. (left) and a reporter at the 1963 Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C.In 1964, he was awarded the Spingarn Medal by the NAACP.[12]

During his tenure, the NAACP played a pivotal role in leading the nation into the Civil Rights Movement and spearheaded the efforts that led to significant civil rights victories, including Brown v. Board of Education, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In 1968, Wilkins also served as chair of the U.S. delegation to the International Conference on Human Rights. After turning 70 in 1971, he faced increased calls to step down as NAACP chief. In 1976, he fell into a dispute with undisclosed board members at the NAACP national convention in Memphis, Tennessee. Although he had intended to retire that year, he decided to postpone it until 1977 because he thought that the pension plan offered to him by the NAACP was inadequate. Board member Emmitt Douglas of Louisiana demanded that Wilkins disclose the offenders and not impugn the board as a whole. Wilkins merely said that the offenders had "vilified" his reputation and questioned his health and integrity.[13]

In 1977, at the age of 76, Wilkins finally retired from the NAACP and was succeeded by Benjamin Hooks.[4] He was honored with the title Director Emeritus of the NAACP in the same year.[2] He died on September 8, 1981 in New York City of heart problems related to a pacemaker implanted on him in 1979 due to his irregular heartbeat.[2] In 1982, his autobiography Standing Fast: The Autobiography of Roy Wilkins was published posthumously.

The players in this drama of frustration and indignity are not commas or semicolons in a legislative thesis; they are people, human beings, citizens of the United States of America.

— Roy WilkinsViewsWilkins was a staunch liberal and proponent of American values during the Cold War, and he denounced suspected and actual communists within the civil rights movement. He had been criticized by some on the left of the civil rights movement, such as Daisy Bates, Paul Robeson, W. E. B. Du Bois, Robert F. Williams, and Fred Shuttlesworth, for his cautious approach, his suspicion of grassroots organizations, and his conciliatory attitude towards white anticommunism.

In 1951, J. Edgar Hoover and the state department, in collusion with the NAACP and Wilkins (then editor of The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP), arranged for a ghost-written leaflet to be printed and distributed in Africa.[14] The purpose of the leaflet was to spread negative press and views about the Black political radical and entertainer Paul Robeson throughout Africa. Roger P. Ross, a State Department public affairs officer working in Africa, issued three pages of detailed guidelines including the following instructions:[15]

United States Information and Educational Exchange (USIE) in the Gold Coast, and I suspect everywhere else in Africa, badly needs a through-going, sympathetic and regretful but straight talking treatment of the whole Robeson episode ... there's no way the Communists score on us more easily and more effectively out here, than on the US. Negro problem in general, and on the Robeson case in particular. And, answering the latter, we go a long way toward answering the former.[14][16]

The finished article published by the NAACP was called Paul Robeson: Lost Shepherd,[17] penned under the false name of "Robert Alan", whom the NAACP claimed was a "well known New York journalist." Another article by Roy Wilkins, called "Stalin's Greatest Defeat", denounced Robeson as well as the Communist Party of the USA in terms consistent with the FBI's information.:[14][15]

At the time of Robeson's widely misquoted[18] declaration at The Paris Peace Conference in 1949, that African Americans would not support the United States in a war with the Soviet Union because of their continued lynchings and second-class citizen status under law following World War II,[19] Roy Wilkins stated that regardless of the number of lynchings that were occurring or would occur, Black America would always serve in the armed forces.[20] Wilkins also threatened to cancel a charter of an NAACP youth group in 1952 if they did not cancel their planned Robeson concert.Stance on War and Military InvolvementDuring the presidential terms of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson the civil rights movement was in its peak. International affairs were somewhat overlooked by numerous members of the NAACP and other civil rights groups in order to focus on domestic issues in the United States. However, Wilkins stayed true to his liberal values and carried these to the White House during his time with the NAACP. Wilkins' friendship and constant correspondence with Johnson gave him an even larger platform to speak out on war efforts and policies affecting civil rights.

His views towards the participation of black military members in the U.S service was a point of contention between him and other prominent civil rights leaders. While most civil rights groups and activists were staying quiet or speaking out against the Vietnam War, Wilkins' was focused on what African-Americans could gain out of serving in the military. An article posted in the Western Journal of Black Studies suggests that black troops were fighting for equality both in the United States as well as overseas. Wilkins emphasized the financial benefits of serving in the military along with the importance of African-American citizens participating in the first integrated American army.[21]

The civil rights movement (also known as the American civil rights movement and other terms)[b] in the United States was a decades-long struggle with the goal of enforcing constitutional and legal rights for African Americans that white Americans already enjoyed. With roots that dated back to the Reconstruction era during the late 19th century, the movement achieved its largest legislative gains in the mid-1960s, after years of direct actions and grassroots protests that were organized from the mid-1950s until 1968. Encompassing strategies, various groups, and organized social movements to accomplish the goals of ending legalized racial segregation, disenfranchisement, and discrimination in the United States, the movement, using major nonviolent campaigns, eventually secured new recognition in federal law and federal protection for all Americans.

After the American Civil War and the abolition of slavery in the 1860s, the Reconstruction Amendments to the United States Constitution granted emancipation and constitutional rights of citizenship to all African Americans, most of whom had recently been enslaved. For a period, African Americans voted and held political office, but they were increasingly deprived of civil rights, often under Jim Crow laws, and subjected to discrimination and sustained violence by whites in the South. Over the following century, various efforts were made by African Americans to secure their legal rights. Between 1955 and 1968, acts of nonviolent protest and civil disobedience produced crisis situations and productive dialogues between activists and government authorities. Federal, state, and local governments, businesses, and communities often had to respond immediately to these situations, which highlighted the inequities faced by African Americans across the country. The lynching of Chicago teenager Emmett Till in Mississippi, and the outrage generated by seeing how he had been abused, when his mother decided to have an open-casket funeral, mobilized the African-American community nationwide.[1] Forms of protest and/or civil disobedience included boycotts, such as the successful Montgomery bus boycott (1955–56) in Alabama; "sit-ins" such as the influential Greensboro sit-ins (1960) in North Carolina and successful Nashville sit-ins in Tennessee; marches, such as the 1963 Birmingham Children's Crusade and 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches (1965) in Alabama; and a wide range of other nonviolent activities.

Moderates in the movement worked with Congress to achieve the passage of several significant pieces of federal legislation that overturned discriminatory practices and authorized oversight and enforcement by the federal government. The Civil Rights Act of 1964[2] expressly banned discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin in employment practices; ended unequal application of voter registration requirements; and prohibited racial segregation in schools, at the workplace, and in public accommodations. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 restored and protected voting rights for minorities by authorizing federal oversight of registration and elections in areas with historic under-representation of minorities as voters. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 banned discrimination in the sale or rental of housing. African Americans re-entered politics in the South, and across the country young people were inspired to take action.

From 1964 through 1970, a wave of inner-city riots in black communities undercut support from the white middle class, but increased support from private foundations.[3] The emergence of the Black Power movement, which lasted from about 1965 to 1975, challenged the established black leadership for its cooperative attitude and its practice of nonviolence. Instead, its leaders demanded that, in addition to the new laws gained through the nonviolent movement, political and economic self-sufficiency had to be developed in the black community.

Many popular representations of the movement are centered on the charismatic leadership and philosophy of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who won the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize for his role in non-violent, moral leadership. However, some scholars note that the movement was too diverse to be credited to any one person, organization, or strategy.[4]Contents1 Background2 The beginnings of direct action (1950s)3 History3.1 Brown v. Board of Education, 19543.2 Emmett Till's murder, 19553.3 Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, 1955–19563.4 Desegregating Little Rock Central High School, 19573.5 The method of Nonviolence and Nonviolence Training3.6 Robert F. Williams and the debate on nonviolence, 1959–19643.7 Sit-ins, 1958–19603.8 Freedom Rides, 19613.9 Voter registration organizing3.10 Integration of Mississippi universities, 1956–19653.11 Albany Movement, 1961–623.12 Birmingham campaign, 19633.13 "Rising tide of discontent" and Kennedy's response, 19633.14 March on Washington, 19633.15 Malcolm X joins the movement, 1964–19653.16 St. Augustine, Florida, 1963–643.17 Chester School Protests, Spring 19643.18 Freedom Summer, 19643.19 Civil Rights Act of 19643.20 Harlem riot of 19643.21 Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, 19643.22 Selma Voting Rights Movement3.23 Voting Rights Act of 19653.24 Watts riot of 19653.25 Fair housing movements, 1966–19683.26 Nationwide riots of 19673.27 Memphis, King assassination and the Poor People's March 19683.28 Civil Rights Act of 19684 Movements, politics, and white reactions4.1 Grassroots leadership4.2 Black power (1966–1968)4.3 Black conservatism4.4 Avoiding the "Communist" label4.5 Kennedy administration, 1961–19634.6 American Jewish community and the civil rights movement4.6.1 Profile4.7 White backlash4.8 African-American women in the movement4.8.1 Discrimination4.9 Long-term impact5 Johnson administration: 1963–19686 Prison reform6.1 Gates v. Collier7 Cold War8 In popular culture9 Activist organizations10 Individual activists11 See also12 Notes13 References14 Bibliography15 Further reading15.1 Historiography and memory15.2 Autobiographies and memoirs16 External linksBackgroundFurther information: Disenfranchisement after the Reconstruction Era, Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Jim Crow laws, Civil rights movement (1865–1896), and Civil rights movement (1896–1954)Before the American Civil War, almost four million blacks were enslaved in the South, only white men of property could vote, and the Naturalization Act of 1790 limited U.S. citizenship to whites only.[5][6][7] Following the Civil War, three constitutional amendments were passed, including the 13th Amendment (1865) that ended slavery; the 14th Amendment (1868) that gave African-Americans citizenship, adding their total population of four million to the official population of southern states for Congressional apportionment; and the 15th Amendment (1870) that gave African-American males the right to vote (only males could vote in the U.S. at the time). From 1865 to 1877, the United States underwent a turbulent Reconstruction Era trying to establish free labor and civil rights of freedmen in the South after the end of slavery. Many whites resisted the social changes, leading to insurgent movements such as the Ku Klux Klan, whose members attacked black and white Republicans to maintain white supremacy. In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant, the U.S. Army, and U.S. Attorney General Amos T. Akerman, initiated a campaign to repress the KKK under the Enforcement Acts.[8] Some states were reluctant to enforce the federal measures of the act. In addition, by the early 1870s, other white supremacist and insurgent paramilitary groups arose that violently opposed African-American legal equality and suffrage, intimidating and suppressing black voters, and assassinating Republican officeholders.[9][10] However, if the states failed to implement the acts, the laws allowed the Federal Government to get involved.[10] Many Republican governors were afraid of sending black militia troops to fight the Klan for fear of war.[10]

After the disputed election of 1876 resulted in the end of Reconstruction and federal troops were withdrawn, whites in the South regained political control of the region's state legislatures. They continued to intimidate and violently attack blacks before and during elections to suppress their voting, but the last African Americans were elected to Congress from the South before disenfranchisement of blacks by states throughout the region, as described below.The mob-style lynching of Will James, Cairo, Illinois, 1909From 1890 to 1908, southern states passed new constitutions and laws to disenfranchise African Americans and many poor whites by creating barriers to voter registration; voting rolls were dramatically reduced as blacks and poor whites were forced out of electoral politics. After the landmark Supreme Court case of Smith v. Allwright (1944), which prohibited white primaries, progress was made in increasing black political participation in the Rim South and Acadiana – although almost entirely in urban areas[11] and a few rural localities where most blacks worked outside plantations.[12] The status quo ante of excluding African Americans from the political system lasted in the remainder of the South, especially North Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama, until national civil rights legislation was passed in the mid-1960s to provide federal enforcement of constitutional voting rights. For more than sixty years, blacks in the South were essentially excluded from politics, unable to elect anyone to represent their interests in Congress or local government.[10] Since they could not vote, they could not serve on local juries.

During this period, the white-dominated Democratic Party maintained political control of the South. With whites controlling all the seats representing the total population of the South, they had a powerful voting bloc in Congress. The Republican Party—the "party of Lincoln" and the party to which most blacks had belonged—shrank to insignificance except in remote Unionist areas of Appalachia and the Ozarks as black voter registration was suppressed. Until 1965, the “Solid South” was a one-party system under the white Democrats. Excepting the previously noted historic Unionist strongholds the Democratic Party nomination was tantamount to election for state and local office.[13] In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt invited Booker T. Washington, president of the Tuskegee Institute, to dine at the White House, making him the first African American to attend an official dinner there. "The invitation was roundly criticized by southern politicians and newspapers."[14] Washington persuaded the president to appoint more blacks to federal posts in the South and to try to boost African-American leadership in state Republican organizations. However, these actions were resisted by both white Democrats and white Republicans as an unwanted federal intrusion into state politics.[14]Lynching victim Will Brown, who was mutilated and burned during the Omaha, Nebraska race riot of 1919. Postcards and photographs of lynchings were popular souvenirs in the U.S.[15]During the same time as African Americans were being disenfranchised, white southerners imposed racial segregation by law. Violence against blacks increased, with numerous lynchings through the turn of the century. The system of de jure state-sanctioned racial discrimination and oppression that emerged from the post-Reconstruction South became to be known as the "Jim Crow" system. The United States Supreme Court, made up almost entirely of Northerners, upheld the constitutionality of those state laws that required racial segregation in public facilities in its 1896 decision Plessy v. Ferguson, legitimizing them through the "separate but equal" doctrine.[16] Segregation, which began with slavery, continued with Jim Crow laws, with signs used to show blacks where they could legally walk, talk, drink, rest, or eat.[17] For those places that were racially mixed, non-whites had to wait until all white customers were served first.[17] Elected in 1912, President Woodrow Wilson gave in to demands by Southern members of his cabinet and ordered segregation of workplaces throughout the federal government.[18]

The early 20th century is a period often referred to as the "nadir of American race relations", when the number of lynchings was highest. While tensions and civil rights violations were most intense in the South, social discrimination affected African Americans in other regions as well.[19] At the national level, the Southern bloc controlled important committees in Congress, defeated passage of federal laws against lynching, and exercised considerable power beyond the number of whites in the South.

Characteristics of the post-Reconstruction period:

Racial segregation. By law, public facilities and government services such as education were divided into separate "white" and "colored" domains.[20] Characteristically, those for colored were underfunded and of inferior quality.Disenfranchisement. When white Democrats regained power, they passed laws that made voter registration more restrictive, essentially forcing black voters off the voting rolls. The number of African-American voters dropped dramatically, and they were no longer able to elect representatives. From 1890 to 1908, Southern states of the former Confederacy created constitutions with provisions that disfranchised tens of thousands of African Americans, and U.S. states such as Alabama disenfranchised poor whites as well.Exploitation. Increased economic oppression of blacks through the convict lease system, Latinos, and Asians, denial of economic opportunities, and widespread employment discrimination.Violence. Individual, police, paramilitary, organizational, and mob racial violence against blacks (and Latinos in the Southwest and Asians in the West Coast).

KKK night rally in Chicago, c. 1920African Americans and other ethnic minorities rejected this regime. They resisted it in numerous ways and sought better opportunities through lawsuits, new organizations, political redress, and labor organizing (see the Civil rights movement (1896–1954)). The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was founded in 1909. It fought to end race discrimination through litigation, education, and lobbying efforts. Its crowning achievement was its legal victory in the Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education (1954) when the Court rejected separate white and colored school systems and, by implication, overturned the "separate but equal" doctrine established in Plessy v. Ferguson of 1896. Segregation had continued intact into the mid-1950s. Following the unanimous Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) that ruled that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional, many states began to gradually integrate their schools, but some areas of the South resisted by closing public schools altogether.

The integration of Southern public libraries followed demonstrations and protests that used techniques seen in other elements of the larger civil rights movement.[21] This included sit-ins, beatings, and white resistance.[21] For example, in 1963 in the city of Anniston, Alabama, two black ministers were brutally beaten for attempting to integrate the public library.[21] Though there was resistance and violence, the integration of libraries was generally quicker than the integration of other public institutions.[21]Colored Sailors room in World War IThe situation for blacks outside the South was somewhat better (in most states they could vote and have their children educated, though they still faced discrimination in housing and jobs). From 1910 to 1970, African Americans sought better lives by migrating north and west out of the South. A total of nearly seven million blacks left the South in what was known as the Great Migration, most during and after World War II. So many people migrated that the demographics of some previously black-majority states changed to white majority (in combination with other developments). The rapid influx of blacks altered the demographics of Northern and Western cities; happening at a period of expanded European, Hispanic, and Asian immigration, it added to social competition and tensions, with the new migrants and immigrants battling for place in jobs and housing.

Reflecting social tensions after World War I, as veterans struggled to return to the workforce and labor unions were organizing, the Red Summer of 1919 was marked by hundreds of deaths and higher casualties across the U.S. as a result of white race riots against blacks that took place in more than three dozen cities, such as the Chicago race riot of 1919 and the Omaha race riot of 1919. Urban problems such as crime and disease were blamed on the large influx of Southern blacks to cities in the north and west, based on stereotypes of rural southern African-Americans. Overall, African Americans in Northern and Western cities experienced systemic discrimination in a plethora of aspects of life. Within employment, economic opportunities for blacks were routed to the lowest-status and restrictive in potential mobility. Within the housing market, stronger discriminatory measures were used in correlation to the influx, resulting in a mix of "targeted violence, restrictive covenants, redlining and racial steering".[22] The Great Migration resulted in many African Americans becoming urbanized, and they began to realign from the Republican to the Democratic Party, especially because of opportunities under the New Deal of the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration during the Great Depression in the 1930s.[23] Substantially under pressure from African-American supporters who began the March on Washington Movement, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued the first federal order banning discrimination and created the Fair Employment Practice Committee. Black veterans of the military after both World Wars pressed for full civil rights and often led activist movements. In 1948, President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981, which eventually led to the end of segregation in the armed services.[24]White tenants seeking to prevent blacks from moving into the housing project erected this sign, Detroit, 1942.Housing segregation was a nationwide problem, widespread outside the South. Although the federal government had become increasingly involved in mortgage lending and development in the 1930s and 1940s, it did not reject the use of race-restrictive covenants until 1950, in part because of provisions by the Solid South Democrats in Congress.[25] Suburbanization became connected with white flight by this time, because whites were better established economically to move to newer housing. The situation was perpetuated by real estate agents' continuing racial discrimination. In particular, from the 1930s to the 1960s, the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB) issued guidelines that specified that a realtor "should never be instrumental in introducing to a neighborhood a character or property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individual whose presence will be clearly detrimental to property values in a neighborhood." The result was the development of all-black ghettos in the North and West, where much housing was older, as well as South.[26]

Invigorated by the victory of Brown and frustrated by the lack of immediate practical effect, private citizens increasingly rejected gradualist, legalistic approaches as the primary tool to bring about desegregation. They were faced with "massive resistance" in the South by proponents of racial segregation and voter suppression. In defiance, African-American activists adopted a combined strategy of direct action, nonviolence, nonviolent resistance, and many events described as civil disobedience, giving rise to the civil rights movement of 1954 to 1968.

The beginnings of direct action (1950s)The strategy of public education, legislative lobbying, and litigation that had typified the civil rights movement during the first half of the 20th century broadened after Brown to a strategy that emphasized "direct action": boycotts, sit-ins, Freedom Rides, marches or walks, and similar tactics that relied on mass mobilization, nonviolent resistance, standing in line, and, at times, civil disobedience.[citation needed]

Churches, local grassroots organizations, fraternal societies, and black-owned businesses mobilized volunteers to participate in broad-based actions. This was a more direct and potentially more rapid means of creating change than the traditional approach of mounting court challenges used by the NAACP and others.

In 1952, the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL), led by T. R. M. Howard, a black surgeon, entrepreneur, and planter, organized a successful boycott of gas stations in Mississippi that refused to provide restrooms for blacks. Through the RCNL, Howard led campaigns to expose brutality by the Mississippi state highway patrol and to encourage blacks to make deposits in the black-owned Tri-State Bank of Nashville which, in turn, gave loans to civil rights activists who were victims of a "credit squeeze" by the White Citizens' Councils.[27]

After Claudette Colvin was arrested for not giving up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama bus in March 1955, a bus boycott was considered and rejected. But when Rosa Parks was arrested in December, Jo Ann Gibson Robinson of the Montgomery Women's Political Council put the bus boycott protest in motion. Late that night, she, John Cannon (chairman of the Business Department at Alabama State University) and others mimeographed and distributed thousands of leaflets calling for a boycott.[28][29] The eventual success of the boycott made its spokesman Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. a nationally known figure. It also inspired other bus boycotts, such as the successful Tallahassee, Florida boycott of 1956–57.[30]

In 1957, Dr. King and Rev. Ralph Abernathy, the leaders of the Montgomery Improvement Association, joined with other church leaders who had led similar boycott efforts, such as Rev. C. K. Steele of Tallahassee and Rev. T. J. Jemison of Baton Rouge, and other activists such as Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, Ella Baker, A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin and Stanley Levison, to form the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The SCLC, with its headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia, did not attempt to create a network of chapters as the NAACP did. It offered training and leadership assistance for local efforts to fight segregation. The headquarters organization raised funds, mostly from Northern sources, to support such campaigns. It made nonviolence both its central tenet and its primary method of confronting racism.

In 1959, Septima Clarke, Bernice Robinson, and Esau Jenkins, with the help of Myles Horton's Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, began the first Citizenship Schools in South Carolina's Sea Islands. They taught literacy to enable blacks to pass voting tests. The program was an enormous success and tripled the number of black voters on Johns Island. SCLC took over the program and duplicated its results elsewhere.

HistoryMain article: Timeline of the civil rights movementFurther information: Civil rights movement (1865–1896) and Civil rights movement (1896–1954)Brown v. Board of Education, 1954Main article: Brown v. Board of EducationIn the spring of 1951, black students in Virginia protested their unequal status in the state's segregated educational system. Students at Moton High School protested the overcrowded conditions and failing facility.[31] Some local leaders of the NAACP had tried to persuade the students to back down from their protest against the Jim Crow laws of school segregation. When the students did not budge, the NAACP joined their battle against school segregation. The NAACP proceeded with five cases challenging the school systems; these were later combined under what is known today as Brown v. Board of Education.[31]

On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, that mandating, or even permitting, public schools to be segregated by race was unconstitutional. The Court stated that the

segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law; for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the Negro group.[32]

The lawyers from the NAACP had to gather plausible evidence in order to win the case of Brown vs. Board of Education. Their method of addressing the issue of school segregation was to enumerate several arguments. One pertained to having exposure to interracial contact in a school environment. It was argued that interracial contact would, in turn, help prepare children to live with the pressures that society exerts in regards to race and thereby afford them a better chance of living in a democracy. In addition, another argument emphasized how "'education' comprehends the entire process of developing and training the mental, physical and moral powers and capabilities of human beings".[33]

Risa Goluboff wrote that the NAACP's intention was to show the Courts that African American children were the victims of school segregation and their futures were at risk. The Court ruled that both Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which had established the "separate but equal" standard in general, and Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education (1899), which had applied that standard to schools, were unconstitutional.

The federal government filed a friend of the court brief in the case urging the justices to consider the effect that segregation had on America's image in the Cold War. Secretary of State Dean Acheson was quoted in the brief stating that "The United States is under constant attack in the foreign press, over the foreign radio, and in such international bodies as the United Nations because of various practices of discrimination in this country." [34][35]

The following year, in the case known as Brown II, the Court ordered segregation to be phased out over time, "with all deliberate speed".[36] Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954) did not overturn Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). Plessy v. Ferguson was segregation in transportation modes. Brown v. Board of Education dealt with segregation in education. Brown v. Board of Education did set in motion the future overturning of 'separate but equal'.School integration, Barnard School, Washington, D.C., 1955On May 18, 1954, Greensboro, North Carolina, became the first city in the South to publicly announce that it would aoffere by the Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education ruling. "It is unthinkable,' remarked School Board Superintendent Benjamin Smith, 'that we will try to [override] the laws of the United States."[37] This positive reception for Brown, together with the appointment of African American Dr. David Jones to the school board in 1953, convinced numerous white and black citizens that Greensboro was heading in a progressive direction. Integration in Greensboro occurred rather peacefully compared to the process in Southern states such as Alabama, Arkansas, and Virginia where "massive resistance" was practiced by top officials and throughout the states. In Virginia, some counties closed their public schools rather than integrate, and many white Christian private schools were founded to accommodate students who used to go to public schools. Even in Greensboro, much local resistance to desegregation continued, and in 1969, the federal government found the city was not in compliance with the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Transition to a fully integrated school system did not begin until 1971.[37]

Many Northern cities also had de facto segregation policies, which resulted in a vast gulf in educational resources between black and white communities. In Harlem, New York, for example, neither a single new school was built since the turn of the century, nor did a single nursery school exist – even as the Second Great Migration was causing overcrowding. Existing schools tended to be dilapidated and staffed with inexperienced teachers. Brown helped stimulate activism among New York City parents like Mae Mallory who, with the support of the NAACP, initiated a successful lawsuit against the city and state on Brown's principles. Mallory and thousands of other parents bolstered the pressure of the lawsuit with a school boycott in 1959. During the boycott, some of the first freedom schools of the period were established. The city responded to the campaign by permitting more open transfers to high-quality, historically-white schools. (New York's African-American community, and Northern desegregation activists generally, now found themselves contending with the problem of white flight, however.)[38][39]

Emmett Till's murder, 1955Main article: Emmett Till

Emmett TillEmmett Till, a 14-year old African American from Chicago, visited his relatives in Money, Mississippi, for the summer. He allegedly had an interaction with a white woman, Carolyn Bryant, in a small grocery store that violated the norms of Mississippi culture, and Bryant's husband Roy and his half-brother J. W. Milam brutally murdered young Emmett Till. They beat and mutilated him before shooting him in the head and sinking his body in the Tallahatchie River. Three days later, Till's body was discovered and retrieved from the river. Mamie Till, Emmett's Mother, "brought him home to Chicago and insisted on an open casket. Tens of thousands filed past Till's remains, but it was the publication of the searing funeral image in Jet, with a stoic Mamie gazing at her murdered child's ravaged body, that forced the world to reckon with the brutality of American racism."[40] Vann R. Newkirk wrote: "The trial of his killers became a pageant illuminating the tyranny of white supremacy".[1] The state of Mississippi tried two defendants, but they were speedily acquitted by an all-white jury.[41]

"Emmett's murder," historian Tim Tyson writes, "would never have become a watershed historical moment without Mamie finding the strength to make her private grief a public matter."[42] The visceral response to his mother's decision to have an open-casket funeral mobilized the black community throughout the U.S.[1] "Young black people such as Julian Bond, Joyce Ladner and others who were born around the same time as Till were galvanized into action by the murder and trial."[42] They often see themselves as the "Emmett Till Generation." One hundred days after Emmett Till's murder, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus in Alabama—indeed, Parks told Mamie Till that "the photograph of Emmett's disfigured face in the casket was set in her mind when she refused to give up her seat on the Montgomery bus."[43] The glass topped casket that was used for Till's Chicago funeral was found in a cemetery garage in 2009. Till had been reburied in a different casket after being exhumed in 2005.[44] Till's family decided to donate the original casket to the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American Culture and History, where it is now on display.[45] In 2007, Bryant disclosed that she had fabricated the most sensational part of her story in 1955.[46][47]

Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, 1955–1956Main articles: Rosa Parks and Montgomery Bus Boycott

Rosa Parks being fingerprinted by Deputy Sheriff D.H. Lackey after being arrested for not giving up her seat on a bus to a white personOn December 1, 1955, nine months after a 15-year-old high school student, Claudette Colvin, refused to give up her seat to a white passenger on a public bus in Montgomery, Alabama, and was arrested, Rosa Parks did the same thing. Parks soon became the symbol of the resulting Montgomery Bus Boycott and received national publicity. She was later hailed as the "mother of the civil rights movement".

Parks was secretary of the Montgomery NAACP chapter and had recently returned from a meeting at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee where nonviolence as a strategy was taught by Myles Horton and others. After Parks' arrest, African Americans gathered and organized the Montgomery Bus Boycott to demand a bus system in which passengers would be treated equally.[48] The organization was led by Jo Ann Robinson, a member of the Women's Political Council who had been waiting for the opportunity to boycott the bus system. Following Rosa Park's arrest, Jo Ann Robinson mimeographed 52,500 leaflets calling for a boycott. They were distributed around the city and helped gather the attention of civil rights leaders. After the city rejected many of their suggested reforms, the NAACP, led by E. D. Nixon, pushed for full desegregation of public buses. With the support of most of Montgomery's 50,000 African Americans, the boycott lasted for 381 days, until the local ordinance segregating African Americans and whites on public buses was repealed. Ninety percent of African Americans in Montgomery partook in the boycotts, which reduced bus revenue significantly, as they comprised the majority of the riders. In November 1956, the United States Supreme Court upheld a district court ruling in the case of Browder v. Gayle and ordered Montgomery's buses desegregated, ending the boycott.[48]

Local leaders established the Montgomery Improvement Association to focus their efforts. Martin Luther King Jr. was elected President of this organization. The lengthy protest attracted national attention for him and the city. His eloquent appeals to Christian brotherhood and American idealism created a positive impression on people both inside and outside the South.[29]

Desegregating Little Rock Central High School, 1957Main article: Little Rock Nine

Troops from the 327th Regiment, 101st Airborne escorting the Little Rock Nine African-American students up the steps of Central HighA crisis erupted in Little Rock, Arkansas, when Governor of Arkansas Orval Faubus called out the National Guard on September 4 to prevent entry to the nine African-American students who had sued for the right to attend an integrated school, Little Rock Central High School.[49] Under the guidance of Daisy Bates, the nine students had been chosen to attend Central High because of their excellent grades.

On the first day of school, 15-year-old Elizabeth Eckford was the only one of the nine students who showed up because she did not receive the phone call about the danger of going to school. A photo was taken of Eckford being harassed by white protesters outside the school, and the police had to take her away in a patrol car for her protection. Afterwards, the nine students had to carpool to school and be escorted by military personnel in jeeps.White parents rally against integrating Little Rock's schools.Faubus was not a proclaimed segregationist. The Arkansas Democratic Party, which then controlled politics in the state, put significant pressure on Faubus after he had indicated he would investigate bringing Arkansas into compliance with the Brown decision. Faubus then took his stand against integration and against the Federal court ruling. Faubus' resistance received the attention of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was determined to enforce the orders of the Federal courts. Critics had charged he was lukewarm, at best, on the goal of desegregation of public schools. But, Eisenhower federalized the National Guard in Arkansas and ordered them to return to their barracks. Eisenhower deployed elements of the 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock to protect the students.

The students attended high school under harsh conditions. They had to pass through a gauntlet of spitting, jeering whites to arrive at school on their first day, and to put up with harassment from other students for the rest of the year. Although federal troops escorted the students between classes, the students were teased and even attacked by white students when the soldiers were not around. One of the Little Rock Nine, Minnijean Brown, was suspended for spilling a bowl of chilli on the head of a white student who was harassing her in the school lunch line. Later, she was expelled for verbally abusing a white female student.[50]

Only Ernest Green of the Little Rock Nine graduated from Central High School. After the 1957–58 school year was over, Little Rock closed its public school system completely rather than continue to integrate. Other school systems across the South followed suit.

The method of Nonviolence and Nonviolence TrainingDuring the time period considered to be the "African-American civil rights" era, the predominant use of protest was nonviolent, or peaceful.[51] Often referred to as pacifism, the method of nonviolence is considered to be an attempt to impact society positively. Although acts of racial discrimination have occurred historically throughout the United States, perhaps the most violent regions have been in the former Confederate states. During the 1950s and 1960s, the nonviolent protesting of the civil rights movement caused definite tension, which gained national attention.

In order to prepare for protests physically and psychologically, demonstrators received training in nonviolence. According to former civil rights activist Bruce Hartford, there are two main branches of nonviolence training. There is the philosophical method, which involves understanding the method of nonviolence and why it is considered useful, and there is the tactical method, which ultimately teaches demonstrators "how to be a protestor—how to sit-in, how to picket, how to defend yourself against attack, giving training on how to remain cool when people are screaming racist insults into your face and pouring stuff on you and hitting you" (Civil Rights Movement Veterans). The philosophical method of nonviolence, in the American civil rights movement, was largely inspired by Mahatma Gandhi's "non-cooperation" with the British colonists in India, which was intended to gain attention so that the public would either "intervene in advance," or "provide public pressure in support of the action to be taken" (Erikson, 415). As Hartford explains it, philosophical nonviolence training aims to "shape the individual person's attitude and mental response to crises and violence" (Civil Rights Movement Veterans). Hartford and activists like him, who trained in tactical nonviolence, considered it necessary in order to ensure physical safety, instill discipline, teach demonstrators how to demonstrate, and form mutual confidence among demonstrators (Civil Rights Movement Veterans).[51][52]

For many, the concept of nonviolent protest was a way of life, a culture. However, not everyone agreed with this notion. James Forman, former SNCC (and later Black Panther) member and nonviolence trainer, was among those who did not. In his autobiography, The Making of Black Revolutionaries, Forman revealed his perspective on the method of nonviolence as "strictly a tactic, not a way of life without limitations." Similarly, Bob Moses, who was also an active member of SNCC, felt that the method of nonviolence was practical. When interviewed by author Robert Penn Warren, Moses said "There's no question that he [Martin Luther King Jr.] had a great deal of influence with the masses. But I don't think it's in the direction of love. It's in a practical direction . . ." (Who Speaks for the Negro? Warren).[53][54]

Robert F. Williams and the debate on nonviolence, 1959–1964The Jim Crow system employed "terror as a means of social control,"[55] with the most organized manifestations being the Ku Klux Klan and their collaborators in local police departments. This violence played a key role in blocking the progress of the civil rights movement in the late 1950s. Some black organizations in the South began practicing armed self-defense. The first to do so openly was the Monroe, North Carolina, chapter of the NAACP led by Robert F. Williams. Williams had rebuilt the chapter after its membership was terrorized out of public life by the Klan. He did so by encouraging a new, more working-class membership to arm itself thoroughly and defend against attack.[56] When Klan nightriders attacked the home of NAACP member Dr. Albert Perry in October 1957, Williams' militia exchanged gunfire with the stunned Klansmen, who quickly retreated. The following day, the city council held an emergency session and passed an ordinance banning KKK motorcades.[57] One year later, Lumbee Indians in North Carolina would have a similarly successful armed stand-off with the Klan (known as the Battle of Hayes Pond) which resulted in KKK leader James W. "Catfish" Cole being convicted of incitement to riot.[58]

After the acquittal of several white men charged with sexually assaulting black women in Monroe, Williams announced to United Press International reporters that he would "meet violence with violence" as a policy. Williams' declaration was quoted on the front page of The New York Times, and The Carolina Times considered it "the biggest civil rights story of 1959."[59] NAACP National chairman Roy Wilkins immediately suspended Williams from his position, but the Monroe organizer won support from numerous NAACP chapters across the country. Ultimately, Wilkins resorted to bribing influential organizer Daisy Bates to campaign against Williams at the NAACP national convention and the suspension was upheld. The convention nonetheless passed a resolution which stated: "We do not deny, but reaffirm the right of individual and collective self-defense against unlawful assaults."[60] Martin Luther King Jr. argued for Williams' removal,[61] but Ella Baker[62] and WEB Dubois[4] both publicly praised the Monroe leader's position.

Williams—along with his wife, Mabel Williams—continued to play a leadership role in the Monroe movement, and to some degree, in the national movement. The Williamses published The Crusader, a nationally circulated newsletter, beginning in 1960, and the influential book Negroes With Guns in 1962. Williams did not call for full militarization in this period, but "flexibility in the freedom struggle."[63] Williams was well-versed in legal tactics and publicity, which he had used successfully in the internationally known "Kissing Case" of 1958, as well as nonviolent methods, which he used at lunch counter sit-ins in Monroe—all with armed self-defense as a complementary tactic.

Williams led the Monroe movement in another armed stand-off with white supremacists during an August 1961 Freedom Ride; he had been invited to participate in the campaign by Ella Baker and James Forman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The incident (along with his campaigns for peace with Cuba) resulted in him being targeted by the FBI and prosecuted for kidnapping; he was cleared of all charges in 1976.[64] Meanwhile, armed self-defense continued discreetly in the Southern movement with such figures as SNCC's Amzie Moore,[64] Hartman Turnbow,[65] and Fannie Lou Hamer[66] all willing to use arms to defend their lives from nightrides. Taking refuge from the FBI in Cuba, the Willamses broadcast the radio show "Radio Free Dixie" throughout the eastern United States via Radio Progresso beginning in 1962. In this period, Williams advocated guerilla warfare against racist institutions, and saw the large ghetto riots of the era as a manifestation of his strategy.

University of North Carolina historian Walter Rucker has written that "the emergence of Robert F Williams contributed to the marked decline in anti-black racial violence in the U.S....After centuries of anti-black violence, African Americans across the country began to defend their communities aggressively—employing overt force when necessary. This in turn evoked in whites real fear of black vengeance..." This opened up space for African Americans to use nonviolent demonstration with less fear of deadly reprisal.[67] Of the many civil rights activists who share this view, the most prominent was Rosa Parks. Parks gave the eulogy at Williams' funeral in 1996, praising him for "his courage and for his commitment to freedom," and concluding that "The sacrifices he made, and what he did, should go down in history and never be forgotten."[68]

Sit-ins, 1958–1960See also: Greensboro sit-ins, Nashville sit-ins, and Sit-in movementIn July 1958, the NAACP Youth Council sponsored sit-ins at the lunch counter of a Dockum Drug Store in downtown Wichita, Kansas. After three weeks, the movement successfully got the store to change its policy of segregated seating, and soon afterwards all Dockum stores in Kansas were desegregated. This movement was quickly followed in the same year by a student sit-in at a Katz Drug Store in Oklahoma City led by Clara Luper, which also was successful.[69]

Mostly black students from area colleges led a sit-in at a Woolworth's store in Greensboro, North Carolina.[70] On February 1, 1960, four students, Ezell A. Blair Jr., David Richmond, Joseph McNeil, and Franklin McCain from North Carolina Agricultural & Technical College, an all-black college, sat down at the segregated lunch counter to protest Woolworth's policy of excluding African Americans from being served food there.[71] The four students purchased small items in other parts of the store and kept their receipts, then sat down at the lunch counter and asked to be served. After being denied service, they produced their receipts and asked why their money was good everywhere else at the store, but not at the lunch counter.[72]

The protesters had been encouraged to dress professionally, to sit quietly, and to occupy every other stool so that potential white sympathizers could join in. The Greensboro sit-in was quickly followed by other sit-ins in Richmond, Virginia;[73] Nashville, Tennessee; and Atlanta, Georgia.[74][75] The most immediately effective of these was in Nashville, where hundreds of well organized and highly disciplined college students conducted sit-ins in coordination with a boycott campaign.[76][77] As students across the south began to "sit-in" at the lunch counters of local stores, police and other officials sometimes used brutal force to physically escort the demonstrators from the lunch facilities.

The "sit-in" technique was not new—as far back as 1939, African-American attorney Samuel Wilbert Tucker organized a sit-in at the then-segregated Alexandria, Virginia, library.[78] In 1960 the technique succeeded in bringing national attention to the movement.[79] On March 9, 1960, an Atlanta University Center group of students released An Appeal for Human Rights as a full page advertisement in newspapers, including the Atlanta Constitution, Atlanta Journal, and Atlanta Daily World.[80] Known as the Committee on Appeal for Human Rights (COAHR), the group initiated the Atlanta Student Movement and began to lead sit-ins starting on March 15, 1960.[75][81] By the end of 1960, the process of sit-ins had spread to every southern and border state, and even to facilities in Nevada, Illinois, and Ohio that discriminated against blacks.

Demonstrators focused not only on lunch counters but also on parks, beaches, libraries, theaters, museums, and other public facilities. In April 1960 activists who had led these sit-ins were invited by SCLC activist Ella Baker to hold a conference at Shaw University, a historically black university in Raleigh, North Carolina. This conference led to the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).[82] SNCC took these tactics of nonviolent confrontation further, and organized the freedom rides. As the constitution protected interstate commerce, they decided to challenge segregation on interstate buses and in public bus facilities by putting interracial teams on them, to travel from the North through the segregated South.[83]

Freedom Rides, 1961Main article: Freedom RiderFreedom Rides were journeys by civil rights activists on interstate buses into the segregated southern United States to test the United States Supreme Court decision Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454 (1960), which ruled that segregation was unconstitutional for passengers engaged in interstate travel. Organized by CORE, the first Freedom Ride of the 1960s left Washington D.C. on May 4, 1961, and was scheduled to arrive in New Orleans on May 17.[84]

During the first and subsequent Freedom Rides, activists travelled through the Deep South to integrate seating patterns on buses and desegregate bus terminals, including restrooms and water fountains. That proved to be a dangerous mission. In Anniston, Alabama, one bus was firebombed, forcing its passengers to flee for their lives.[85]A mob beats Freedom Riders in Birmingham. This picture was reclaimed by the FBI from a local journalist who also was beaten and whose camera was smashed.In Birmingham, Alabama, an FBI informant reported that Public Safety Commissioner Eugene "Bull" Connor gave Ku Klux Klan members fifteen minutes to attack an incoming group of freedom riders before having police "protect" them. The riders were severely beaten "until it looked like a bulldog had got a hold of them." James Peck, a white activist, was beaten so badly that he required fifty stitches to his head.[85]

In a similar occurrence in Montgomery, Alabama, the Freedom Riders followed in the footsteps of Rosa Parks and rode an integrated Greyhound bus from Birmingham. Although they were protesting interstate bus segregation in peace, they were met with violence in Montgomery as a large, white mob attacked them for their activism. They caused an enormous, 2-hour long riot which resulted in 22 injuries, five of whom were hospitalized.[86]

Mob violence in Anniston and Birmingham temporarily halted the rides. SNCC activists from Nashville brought in new riders to continue the journey from Birmingham to New Orleans. In Montgomery, Alabama, at the Greyhound Bus Station, a mob charged another bus load of riders, knocking John Lewis unconscious with a crate and smashing Life photographer Don Urbrock in the face with his own camera. A dozen men surrounded James Zwerg, a white student from Fisk University, and beat him in the face with a suitcase, knocking out his teeth.[85]

On May 24, 1961, the freedom riders continued their rides into Jackson, Mississippi, where they were arrested for "breaching the peace" by using "white only" facilities. New Freedom Rides were organized by many different organizations and continued to flow into the South. As riders arrived in Jackson, they were arrested. By the end of summer, more than 300 had been jailed in Mississippi.[84]

.. When the weary Riders arrive in Jackson and attempt to use "white only" restrooms and lunch counters they are immediately arrested for Breach of Peace and Refusal to Obey an Officer. Says Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett in defense of segregation: "The Negro is different because God made him different to punish him." From lockup, the Riders announce "Jail No Bail"—they will not pay fines for unconstitutional arrests and illegal convictions—and by staying in jail they keep the issue alive. Each prisoner will remain in jail for 39 days, the maximum time they can serve without loosing [sic] their right to appeal the unconstitutionality of their arrests, trials, and convictions. After 39 days, they file an appeal and post bond...[87]

The jailed freedom riders were treated harshly, crammed into tiny, filthy cells and sporadically beaten. In Jackson, some male prisoners were forced to do hard labor in 100 °F heat. Others were transferred to the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, where they were treated to harsh conditions. Sometimes the men were suspended by "wrist breakers" from the walls. Typically, the windows of their cells were shut tight on hot days, making it hard for them to breathe.

Public sympathy and support for the freedom riders led John F. Kennedy's administration to order the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to issue a new desegregation order. When the new ICC rule took effect on November 1, 1961, passengers were permitted to sit wherever they chose on the bus; "white" and "colored" signs came down in the terminals; separate drinking fountains, toilets, and waiting rooms were consolidated; and lunch counters began serving people regardless of skin color.

The student movement involved such celebrated figures as John Lewis, a single-minded activist; James Lawson, the revered "guru" of nonviolent theory and tactics; Diane Nash, an articulate and intrepid public champion of justice; Bob Moses, pioneer of voting registration in Mississippi; and James Bevel, a fiery preacher and charismatic organizer, strategist, and facilitator. Other prominent student activists included Charles McDew, Bernard Lafayette, Charles Jones, Lonnie King, Julian Bond, Hosea Williams, and Stokely Carmichael.

Voter registration organizingAfter the Freedom Rides, local black leaders in Mississippi such as Amzie Moore, Aaron Henry, Medgar Evers, and others asked SNCC to help register black voters and to build community organizations that could win a share of political power in the state. Since Mississippi ratified its new constitution in 1890 with provisions such as poll taxes, residency requirements, and literacy tests, it made registration more complicated and stripped blacks from voter rolls and voting. Also, violence at the time of elections had earlier suppressed black voting.

By the mid-20th century, preventing blacks from voting had become an essential part of the culture of white supremacy. In June and July 1959, members of the black community in Fayette County, TN formed the Fayette County Civic and Welfare League to spur voting. At the time, there were 16,927 blacks in the county, yet only 17 of them had voted in the previous seven years. Within a year, some 1,400 blacks had registered, and the white community responded with harsh economic reprisals. Using registration rolls, the White Citizens Council circulated a blacklist of all registered black voters, allowing banks, local stores, and gas stations to conspire to deny registered black voters essential services. What's more, sharecropping blacks who registered to vote were getting evicted from their homes. All in all, the number of evictions came to 257 families, many of whom were forced to live in a makeshift Tent City for well over a year. Finally, in December 1960, the Justice Department invoked its powers authorized by the Civil Rights Act of 1957 to file a suit against seventy parties accused of violating the civil rights of black Fayette County citizens.[88] In the following year the first voter registration project in McComb and the surrounding counties in the Southwest corner of the state. Their efforts were met with violent repression from state and local lawmen, the White Citizens' Council, and the Ku Klux Klan. Activists were beaten, there were hundreds of arrests of local citizens, and the voting activist Herbert Lee was murdered.[89]

White opposition to black voter registration was so intense in Mississippi that Freedom Movement activists concluded that all of the state's civil rights organizations had to unite in a coordinated effort to have any chance of success. In February 1962, representatives of SNCC, CORE, and the NAACP formed the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO). At a subsequent meeting in August, SCLC became part of COFO.[90]

In the Spring of 1962, with funds from the Voter Education Project, SNCC/COFO began voter registration organizing in the Mississippi Delta area around Greenwood, and the areas surrounding Hattiesburg, Laurel, and Holly Springs. As in McComb, their efforts were met with fierce opposition—arrests, beatings, shootings, arson, and murder. Registrars used the literacy test to keep blacks off the voting rolls by creating standards that even highly educated people could not meet. In addition, employers fired blacks who tried to register, and landlords evicted them from their rental homes.[91] Despite these actions, over the following years, the black voter registration campaign spread across the state.

Similar voter registration campaigns—with similar responses—were begun by SNCC, CORE, and SCLC in Louisiana, Alabama, southwest Georgia, and South Carolina. By 1963, voter registration campaigns in the South were as integral to the Freedom Movement as desegregation efforts. After the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,[2] protecting and facilitating voter registration despite state barriers became the main effort of the movement. It resulted in passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which had provisions to enforce the constitutional right to vote for all citizens.

Integration of Mississippi universities, 1956–1965Beginning in 1956, Clyde Kennard, a black Korean War-veteran, wanted to enroll at Mississippi Southern College (now the University of Southern Mississippi) at Hattiesburg under the G.I. Bill. Dr. William David McCain, the college president, used the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, in order to prevent his enrollment by appealing to local black leaders and the segregationist state political establishment.[92]

The state-funded organization tried to counter the civil rights movement by positively portraying segregationist policies. More significantly, it collected data on activists, harassed them legally, and used economic boycotts against them by threatening their jobs (or causing them to lose their jobs) to try to suppress their work.

Kennard was twice arrested on trumped-up charges, and eventually convicted and sentenced to seven years in the state prison.[93] After three years at hard labor, Kennard was paroled by Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett. Journalists had investigated his case and publicized the state's mistreatment of his colon cancer.[93]

McCain's role in Kennard's arrests and convictions is unknown.[94][95][96][97] While trying to prevent Kennard's enrollment, McCain made a speech in Chicago, with his travel sponsored by the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission. He described the blacks' seeking to desegregate Southern schools as "imports" from the North. (Kennard was a native and resident of Hattiesburg.) McCain said:

We insist that educationally and socially, we maintain a segregated society...In all fairness, I admit that we are not encouraging Negro voting...The Negroes prefer that control of the government remain in the white man's hands.[94][96][97]

Note: Mississippi had passed a new constitution in 1890 that effectively disfranchised most blacks by changing electoral and voter registration requirements; although it deprived them of constitutional rights authorized under post-Civil War amendments, it survived U.S. Supreme Court challenges at the time. It was not until after passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that most blacks in Mississippi and other southern states gained federal protection to enforce the constitutional right of citizens to vote.James Meredith walking to class accompanied by U.S. marshalsIn September 1962, James Meredith won a lawsuit to secure admission to the previously segregated University of Mississippi. He attempted to enter campus on September 20, on September 25, and again on September 26. He was blocked by Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett, who said, "[N]o school will be integrated in Mississippi while I am your Governor." The Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals held Barnett and Lieutenant Governor Paul B. Johnson Jr. in contempt, ordering them arrested and fined more than $10,000 for each day they refused to allow Meredith to enroll.[98]U.S. Army trucks loaded with U.S. Marshals on the University of Mississippi campusAttorney General Robert Kennedy sent in a force of U.S. Marshals. On September 30, 1962, Meredith entered the campus under their escort. Students and other whites began rioting that evening, throwing rocks and firing on the U.S. Marshals guarding Meredith at Lyceum Hall. Two people, including a French journalist, were killed; 28 marshals suffered gunshot wounds, and 160 others were injured. President John F. Kennedy sent regular U.S. Army forces to the campus to quell the riot. Meredith began classes the day after the troops arrived.[99]

Kennard and other activists continued to work on public university desegregation. In 1965 Raylawni Branch and Gwendolyn Elaine Armstrong became the first African-American students to attend the University of Southern Mississippi. By that time, McCain helped ensure they had a peaceful entry.[100] In 2006, Judge Robert Helfrich ruled that Kennard was factually innocent of all charges for which he had been convicted in the 1950s.[93]

Albany Movement, 1961–62Main article: Albany MovementThe SCLC, which had been criticized by some student activists for its failure to participate more fully in the freedom rides, committed much of its prestige and resources to a desegregation campaign in Albany, Georgia, in November 1961. King, who had been criticized personally by some SNCC activists for his distance from the dangers that local organizers faced—and given the derisive nickname "De Lawd" as a result—intervened personally to assist the campaign led by both SNCC organizers and local leaders.

The campaign was a failure because of the canny tactics of Laurie Pritchett, the local police chief, and divisions within the black community. The goals may not have been specific enough. Pritchett contained the marchers without violent attacks on demonstrators that inflamed national opinion. He also arranged for arrested demonstrators to be taken to jails in surrounding communities, allowing plenty of room to remain in his jail. Pritchett also foresaw King's presence as a danger and forced his release to avoid King's rallying the black community. King left in 1962 without having achieved any dramatic victories. The local movement, however, continued the struggle, and it obtained significant gains in the next few years.[101]

Birmingham campaign, 1963Main article: Birmingham campaignThe Albany movement was shown to be an important education for the SCLC, however, when it undertook the Birmingham campaign in 1963. Executive Director Wyatt Tee Walker carefully planned the early strategy and tactics for the campaign. It focused on one goal—the desegregation of Birmingham's downtown merchants, rather than total desegregation, as in Albany.

The movement's efforts were helped by the brutal response of local authorities, in particular Eugene "Bull" Connor, the Commissioner of Public Safety. He had long held much political power but had lost a recent election for mayor to a less raofferly segregationist candidate. Refusing to accept the new mayor's authority, Connor intended to stay in office.

The campaign used a variety of nonviolent methods of confrontation, including sit-ins, kneel-ins at local churches, and a march to the county building to mark the beginning of a drive to register voters. The city, however, obtained an injunction barring all such protests. Convinced that the order was unconstitutional, the campaign defied it and prepared for mass arrests of its supporters. King elected to be among those arrested on April 12, 1963.[102]

While in jail, King wrote his famous "Letter from Birmingham Jail"[103] on the margins of a newspaper, since he had not been allowed any writing paper while held in solitary confinement.[104] Supporters appealed to the Kennedy administration, which intervened to obtain King's release. King was allowed to call his wife, who was recuperating at home after the birth of their fourth child and was released early on April 19.

The campaign, however, faltered as it ran out of demonstrators willing to risk arrest. James Bevel, SCLC's Director of Direct Action and Director of Nonviolent Education, then came up with a bold and controversial alternative: to train high school students to take part in the demonstrations. As a result, in what would be called the Children's Crusade, more than one thousand students skipped school on May 2 to meet at the 16th Street Baptist Church to join the demonstrations. More than six hundred marched out of the church fifty at a time in an attempt to walk to City Hall to speak to Birmingham's mayor about segregation. They were arrested and put into jail. In this first encounter, the police acted with restraint. On the next day, however, another one thousand students gathered at the church. When Bevel started them marching fifty at a time, Bull Connor finally unleashed police dogs on them and then turned the city's fire hoses water streams on the children. National television networks broadcast the scenes of the dogs attacking demonstrators and the water from the fire hoses knocking down the schoolchildren.[105]

Widespread public outrage led the Kennedy administration to intervene more forcefully in negotiations between the white business community and the SCLC. On May 10, the parties announced an agreement to desegregate the lunch counters and other public accommodations downtown, to create a committee to eliminate discriminatory hiring practices, to arrange for the release of jailed protesters, and to establish regular means of communication between black and white leaders.

Not everyone in the black community approved of the agreement—the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth was particularly critical, since he was skeptical about the good faith of Birmingham's power structure from his experience in dealing with them. Parts of the white community reacted violently. They bombed the Gaston Motel, which housed the SCLC's unofficial headquarters, and the home of King's brother, the Reverend A. D. King. In response, thousands of blacks rioted, burning numerous buildings and one of them stabbed and wounded a police officer.[106]Congress of Racial Equality march in Washington D.C. on September 22, 1963, in memory of the children killed in the Birmingham bombingsKennedy prepared to federalize the Alabama National Guard if the need arose. Four months later, on September 15, a conspiracy of Ku Klux Klan members bombed the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, killing four young girls.